|

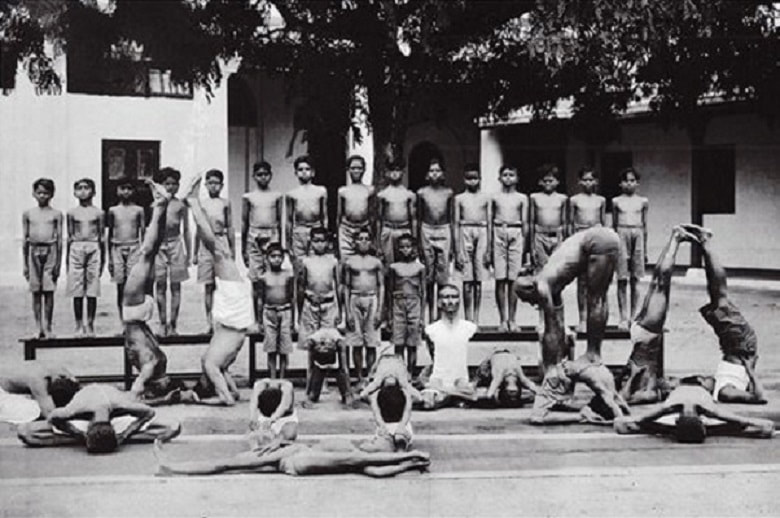

Still waiting for a non-hierarchical and feminist yoga? This post about whiteness, womanhood and other serious yoga issues is done as a conversation between myself and my partner and fellow yoga practitioner Alan O'Leary. The dialogue was inspired by an article on similar themes by Rumya Putcha. I hope you find it interesting, and I invite you to comment below. Marie writes: Alan, I recently sent you this blog article called Yoga and the Maintenance of White Womanhood, written by Rumya Putcha (a ‘Brown woman’ in America, as she describes herself on the blog), which deals with subjects of whiteness, womanhood, rituals and cultural appropriation. Reading the article encouraged me to do self reflection on my role as a white woman teaching and practicing yoga. How should I change my behaviour in the light of Putcha’s article and statements like ‘the colonization of yoga by White women is a shining example [...] of white supremacy’? You and I started discussing the content of this article at the dinner table, exchanging views on the use of ‘Namaste’ at the end of a yoga class and what it means to be a white woman (or man) teaching yoga to white people. These themes have featured in our conversations before but the article fired up this discussion and hit a nerve with me. Rather than diving into a monologue, I thought I’d invite you to write a blog post with me where you can add an additional voice (from the position of another gender) on these important subjects. Together we can think about the article and the issues it deals with. Also, we have had fun with this format in the past when we jointly shared our experiences of a Richard Freeman intensive in London in 2012. See post here. I would like to keep the conversation as an informal ‘ping-pong’ where we can respond to each other’s comments and allow the conversation to develop and change direction. I hope you will join me. Let me begin the conversation by asking you about the use of Sanskrit and Indian languages in yoga classes. What does the use of the greeting ‘Namaste’ at the end of a yoga practice or the invocation (the chant) at the beginning of an Ashtanga/mysore practice mean to you? Alan: Thanks for the invitation, Marie. Rumya Putcha’s article was very interesting: astute and challenging and with a very telling choice of illustrations, and it does resonate with the conversations we have been having for a while about the role of ritual and language(s) around the practice, and things like the ‘interior design’ of yoga spaces. In answering your question, I will leave aside for the moment issues of cultural appropriation and orientalism (stereotypical representations of the East) that Putcha addresses, and try to treat sympathetically the rituals of yoga spaces, which have been predominantly female spaces in my experience. As a man, I have often felt like something of an interloper or a guest in such spaces, and it isn’t appropriate to jeer at the habits of one’s hosts! So I have always tried to chant along, to return the ‘namaste’, and to listen politely, even as I impatiently waited to stretch, while the teacher jabbed at a harmonium (!) or dilated on the day’s lessons for our spiritual well-being… But, yes, I admit to finding much of this stuff absurd. Partly, my impatience has to do with a typically masculine appeal to ‘facts’ (of which I am ashamed). The Ashtanga opening chant, for example, is part of a discourse that insists on the direct relationship of modern postural practice to classical yoga teaching and especially the writings of Patanjali, author of the Yogasūtras. Scholarship has demonstrated this relationship to be a myth (see especially the book Yoga Body, by Mark Singleton), and shown how the postural ‘yoga’ we practice (and love) draws from a variety of traditions, from ‘esoteric dance’ to British military gymnastics as well as from the limited posture component of Indian Hatha traditions. The assertions made about the spirituality of the practice seem to me, in the light of this scholarship, to be incoherent and I don’t see why we should be forced to imbibe a garbled version of Indian religious philosophy at the same time as we try to build our core strength...  Joey adjusting Marie in Kapotasana Joey adjusting Marie in Kapotasana Marie: Surely, to speak of ‘garbled philosophy’ is unfair, Alan. Many people are genuinely attracted to the meditative and spiritual aspects of yoga even as they value its physical health benefits, and they appreciate their teachers being knowledgeable . Maybe they don’t make the dualistic distinction you seem to be making between body (‘core strength’) and mind (‘philosophy’)? Alan: Touché! I certainly don’t mean to play the dualist in this duel! It’s rather that I don’t recognise that there is a necessary or inevitable relationship between postural practice and a greatest hits selection of Indian philosophy. Try this as an experiment: the next time, instead of the Ashtanga chant - which refers not altogether accessibly to the elimination of the delusion caused by the poisonous herb of Samsara - try to begin the practice with the Lord’s Prayer. (After all, if the Ashtanga practice also derives from the Christian tradition of British military gymnastics, why not?) If you practice fervently in the light of the words, ‘your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven’, I think you will find your awareness enriched and posture practice deepened as you attempt to embody divine will in your movements on the mat. I mean that suggestion both sincerely and satirically. Sincerely, because the attempt to practice according to an uplifting phrase lends focus and resilience and the sense of higher purpose that is a key component of stamina. Satirically, because I think it doesn’t matter what the content of that uplifting phrase might be! The Ashtanga chant, the Lord’s Prayer, the words of a Talking Heads song (I often hum ‘I’m still waiting, I’m still waiting…’ to myself as I fail to catch my toes in Kapotansana - it gifts me a profound sense of acceptance). Of course, the opening Ashtanga chant does ‘seal’ the space - it signals that we should forget our woes, worries and the world to engage in a focussed activity. Maybe the challenge should be to develop some non-denominational short discourse to open a lesson and to perform a similar ‘sealing’ of the space and activity, and to honour the teachers that have handed on the practice as the Ashtanga chant does, in its noble but cryptic text. (Or, if that sounds naff, maybe not! Maybe sitting quietly is enough!) Marie writes: I think you’re playing the devil’s advocate here. As I say, it doesn’t seem right to me to dismiss completely the importance of Indian traditions and values and the spiritual aspects in the yoga shala that represent the foundation of yoga. I can say for myself that the ‘otherness’ I experienced of stepping into a yoga space has had a profound impact on me. By ‘otherness’ I mean traditions and rituals so far from what I already knew. When I first entered a dedicated yoga shala It was like nothing else I’d ever experienced: you take your shoes off; you talk quietly if at all; you sit alone on your mat with your eyes closed and the lights are dimmed; there might even be a smell of incense. It was exotic, and for me the exoticism helped me step outside of my own comfort zone and surrender to the practice. This otherness which, yes, could be a disguised orientalism, has opened a door into my own somatic journey where activities I enjoy, like meditation or deep stretching, is not seen as weird or abnormal. I agree that the opening mantra of the Ashtanga Yoga practice feels arbitrary as I only have a notional idea of its literal translation or the overall meaning. I do not think I would exchange if for the Lord’s Prayer though!! I know you were being provocative and I understand your point about the embodiment of the divine and wonder what could replace it… I do feel that the marking of the space and the entrance into the journey of this practice (together with others) gives a sense of community and it brings a group together. I would also like to interrogate the term ‘spirituality’. I personally dislike this term as it has come to mean so many different things and I am not even sure anymore if it is the right word to use to explain what I experience or ‘look for’ in my practice and teaching. I suppose it has religious connotation which is perhaps why it doesn’t sit right with me. Stuart Ray Sarbacker describes well, in his article ‘Reclaiming the Spirit through the Body: The Nascent Spirituality of Modern Postural Yoga’, what he call the ‘physical-spiritual dynamics’ that ‘“bridges the gap” between body and mind and spirit’ (p. 102). I know from my own postural practice that challenging myself through the depth of the postures has had an impact on my perception of myself. I remember getting into Supta Kurmasana for the first time and thinking to myself (while trying to breath) that I could not understand how my body was able to do that. When I teach now and help someone to bind in Marychasana C for the first time I can see they experience something similar: ‘I never believed my body could do this.’ It may not be a ‘spiritual’ experience but I do believe that the experience of your body moving in a direction you could never have imagined opens your mind to other things you could not have imagined: like speaking in public or taking on a new job. Alan writes: I take your point. I am particularly struck by what you say about how ‘otherness’ might be a way in to a ‘somatic journey’. And I agree, of course, with how you describe what the practice teaches you - the confidence and sense of adventure it gives you. What I object to is the mystification of the practice. I don’t think it needs the religious or even the ‘spiritual’ accoutrements that have become de rigueur. Actually, I think these trimmings are an obstacle to the achievement of the confidence you describe, and I suspect they are a turnoff for many potentially dedicated practitioners. I suppose I’m asking for a securalized and non-denominational practice and practice environment. After all, if we want yoga to be inclusive, why are we excluding religious people from other traditions - or at least making them and secularists like myself uncomfortable - by decorating our studios with a mishmash of Hindu and Buddhist statuary? Part of the reason I say this is that the Hindu nationalist government in India has been instrumentalizing yoga as a majority Hindu practice seen as intrinsic to Indian identity. This makes it very clear how yoga can be mobilized symbolically against, say, the Indian Muslim minority. Are we comfortable asking our Muslim students to speak and even pray in the words of a tradition that continues to discriminate, and much worse, against their brothers and sisters? Marie: And may I add here my discomfort of practicing – and indeed chanting – in front of a photograph of the late Pattabhi Jois who as we know has recently been accused of sexual misconduct (see this article by Matthew Remski, Yoga’s Culture of Sexual Abuse).  Iyengar in Yoganidrasana Iyengar in Yoganidrasana Alan: Your mention of the public discussion about Pattabhi Jois’ abuse of his female students opens a set of questions that have to be added to the questions of cultural appropriation and orientalism raised in her blog by Rumya Putcha. Perhaps it’s matter for another discussion, but the fact that Jois’ violence to female students was tacitly condoned by something like the whole practicing community suggests something fundamentally wrong with the ‘guru’ model that is aspired to (mainly) by male teachers in our predominantly female yoga spaces. It also means that the community needs to have an honest discussion about the culture of strong adjustments in Ashtanga (honest not least about any pain or injury that might have been caused). One question raised by the article on the culture of sexual abuse you mention is whether there a continuum between the violence of the sexual assaults perpetrated by the founder of the Ashtanga system, and the firmness of the adjustments performed as standard by teachers of that system. Maybe not - maybe to suggest as much is to fail to recognise the ‘distinctiveness’ of the violation experienced by the victims of sexual assault. But I think we, as a community of practice, need to think about this question, and radically to reconsider the status (and therefore the power and responsibility) we confer our teachers. At the very least, there needs to be a far far greater emphasis in our community of practice on non-violence in the performance of adjustments, and the necessity for the teacher performing them to do so without ego. Marie: I agree that the subject of sexual violence in the yoga community is beyond the scope of what we’re trying to do for this post; it just felt necessary to mention my own unease at Jois’ photo where I practice and teach. I don’t feel comfortable making connections between sexual abuse and firmness of adjustments so I won’t comment further on this. But I agree it’s a fine line when assisting someone in Yoganidrasana (folding both legs behind your head while lying on your back) to avoid touching inappropriately. I was left completely aghast with the scope of the allegations of sexual abuse in the yoga world when I read Remski’s article. I was not aware of the extent this was happening. I had the same reaction when I read this article as when the #MeToo campaign erupted: ‘I’m so glad nothing ever happened to me’ until I let my mind wonder and suddenly remembered a few episodes of being unsure of a (male) teacher’s intentions with an adjustment or even just making sure never to be alone with one particular teacher. Nothing where I could ever put a finger on a specific assault but just a culture where certain behaviour is acceptable. Alan: And plainly, such a culture is unacceptable! And the Ashtanga dogma - just to limit ourselves to our own practice - that tries to petrify the practice (by insisting it must be done just so and must not be changed) is fertile ground for such a culture. But I want to return to the article by Putcha, which as I say, I found very astute and powerful. I think it identifies very well how seemingly ‘innocent’ and positive activities are implicated in the reproduction of social and racial hierarchies (and in this case, ideologies and practices of white supremacy). But I think it needs to be acknowledged that white women are regularly made the scapegoats of an inability to conceptualise structural racism. If you can’t think through the systemic aspects of racism in our world (and it is difficult to think in terms of structure and system), then it’s all too easy to demonize individuals, especially those who belong to a category also subject to systemic abuse - white women in this case. (We have been reminded by recent events, to do with the election of a certain beer-loving justice to the US supreme court, that even very privileged white women are routinely attacked and dismissed.) Putcha’s blog doesn’t avoid this kind of scapegoating, it seems to me, and it’s revealing that she appeals to the opinions of two male white yoga practitioners to support her argument. Of course, it’s not for me, another male white to adjudicate! The default deference to male ‘authority’ - teacher, guru, boss, supreme court justice… - is the source of the problem not the solution… Marie: You say above that yoga is (or has become) women’s territory. Putcha, I think, asserts this in her article. Is it because yoga is seen as ‘women’s work’ that it is acceptable to doubt its importance and value (it is a well known issue that jobs, like nursing and primary school teaching, associated with woman have low status and are not well paid)? A comment made after the article by someone calling themselves ‘projectrevo’ reads: ‘Yoga is not a career and it certainly isn’t something to profit from. Ironically something you learn from practicing yoga itself lol, which white women always overlook’. I think this comment illustrates my point. As you mention above, Alan, Putcha invokes the opinions of male (white) teachers to underpin her argument. I am myself guilty of this. How often do I read, quote or refer to female role models in yoga? Practically never. You and I come from a tradition of many male teachers (most of the big names in Ashtanga Yoga are male) so being a woman teaching Ashtanga Yoga feels important. Alan: I strongly agree that ensuring diversity of leadership is essential for an ethical and sustaining practice community where all are enabled to thrive. And I think the more serious issue of cultural appropriation (more serious, that is, than that of white women greeting each other with ‘Namaste’) is of white male teachers setting themselves up as guru figures. As Matthew Remski's article suggests, we need a non-hierarchical and a feminist yoga… Marie: Yes, but would the achievement of that noble ideal (which I support!) solve the problem of appropriation and of the complicity of yoga in the West in sustaining what Putcha calls white supremacy? Personally, I am embarrassed to say that it never occured to me that I was appropriating a culture by teaching yoga with the use of Sanskrit names or Indian gestures. So Putcha’s article hit a nerve with me and made me reconsider all sorts of rituals I exercise and ideas I have about my yoga teaching and practicing. I stopped using ‘Namaste’ altogether some time ago, it felt really odd and out of place in the contexts I was teaching. After reading Putcha’s article it has become clearer for me why I felt like that. The Danish people I began teaching in 2017, many of them new to yoga, were clearly coming to yoga classes for the benefits that you mention above, like physical health and also de-stressing, so using Indian terminology felt inappropriate. However, I do think it is valuable and just to acknowledge and pay tribute to the Indian origins of the practice. What is a good way to do this without appropriating another culture? I still place my hands together in front of my heart at the end of every class and invite my students to do the same. This gesture is very ‘un-Danish’ and borders ‘exoticism’ but I have yet to find another simple way to express gratitude and respect without words. It’s true that I don’t chant before teaching a led class, but I do when I teach Mysore self-practice; unlike you, Alan, I find the ritual of joining together with voices marks the beginning of a shared journey as we set off on a practice on our individual mats. Alan: Yes, it is right and proper to foreground the Indian origins of the practice, and indeed of ideas like non-violence (Ahimsa) which I've been using here. However, I think this needs to be done in a way that treats those origins in terms of modernity and innovation rather than antiquity and tradition. Figures like Krishnamacharya and his students including Indra Devi, BKS Iyengar and (yes) Pattabhi Jois were great innovators, combining and evolving a variety of postural traditions fit for a changing world and an expanding range of practitioners. Is Sanskrit the best vehicle to acknowledge this? I want to finish though by returning to the question of orientalism and exoticism. You have used the latter word just now in an apologetic way, but let me repeat that I think what you have said above about the power of otherness is a really important point. The encounter with the exotic is a way to challenge and change oneself and to imagine a different world precisely in the practice of oneself. As Victor Segalen wrote many years ago: ‘Exoticism’s power is nothing other than the ability to conceive otherwise.’ So I would distinguish the exotic from the orientalist, which is instead a way of normalizing power inequalities and exploitation. Orientalism is a set of stereotypical representations and ideas about the East. I think one of these orientalist stereotypes is partly responsible for the culture of tolerance of sexual assault in yoga that is belatedly being publicly named and denounced. I have in mind the way that India is seen in the West to be historically ‘behind’ us - to be somehow located in a more spiritual/mystical moment in the past (what is known as the ‘denial of coevalness’). Perhaps, as a result of this stereotype, a person like Pattabhi Jois was not held to the same ethical standards as a ‘Western’ teacher - as if a ‘backward Oriental’ couldn’t be held responsible for his behaviour? My closing questions would be as follows. Are (a) the tolerance of sexual assault and (b) the appropriation of the picturesque elements of Indian culture for the purposes of adorning whiteness part of the same phenomenon? Do they both rely on an idea of India as non-modern and non-contemporary to us? And to what extent does this stereotypical orientalist perception underpin the assumptions and practices of white supremacy that Putcha so effectively denounces? How can we pay tribute to the Indian roots of postural yoga while acknowledging the hybridity of those origins and emphasising their innovatory and modern character? Marie: Thanks Alan for joining me in this conversation. Much more could be said about these issues but let’s leave it there. I think it’s worth repeating that the purpose of this dialogue has been to have an open dialogue about subjects we often talk about in private but that are not often discussed in public. Neither of us have the answers - and this conversation is a tentative way to share the intuitions and feelings and conversations we have had about the culture of yoga and especially about the macho or cultist or unmindful aspects of the culture of Ashtanga yoga - the practice we have most loved, and to which we are still indebted. What will change from this I ask myself? How can I take my thinking on these issues and employ them in my work as a teacher of yoga? I have let go of the ‘Namaste’... perhaps the next step is to reconsider the opening chant for the Mysore classes? But no Alan, not some version of a song by Talking Heads!

6 Comments

Claire Launchbury

23/10/2018 15:53:11

It's bizarre, I was thinking about the Ashtanga chant/prayer on the way back from the dentists yesterday before I read this because my iPod shuffled to Madonna's track which features it from Ray of Light. First, I thought it was sort of weird, and an epitome of a sort of western commercialisation of sorts and second I thought, I bet Madonna is amazing at ashtanga. But those points you and Alan raise are all fascinating. On Namaste, it's the greeting you get (obviously) on Air India, but as Alan points out about the Hindu majority misusing yoga politically, a friend from the Muslim minority was extremely concerned about the airline proposing to serve only vegetarian food on domestic flights - seeing it as another form of political erasure of her identity. I rather like the ritual in order to open the space to the practice but then I also own mala beads and have a lotus flower tattooed on my shoulder (by a Maori guy in Bondi) so drank the Sydney Eastern suburb koolaid a while ago, but any sort of 'spirituality' in that colonial settler society seems loaded with appropriation... I am interested in the thinking about practice and the discipline that goes with that and how that can invest life beyond the mat - in practices of not harming, truthfulness, in behaviour that resounds with being a good citizen, of civic duty - which might square a secular circle or not... good to read you!

Reply

Marie

7/11/2018 11:24:57

Thanks Claire for your useful and insightful comments and for expanding on the political issues of this post. Like you i feel caught between my acknowledgment of certain cultural appropriation and my rejection of it for political reasons. It is so complex. Really appreciate your feedback

Reply

Helen Ince

28/10/2018 11:54:48

Thank you so much for this, such a fascinating read.

Reply

Marie

7/11/2018 11:29:09

Thanks for your comments and honesty. It is hard to navigate the opposition between what has become a ritual that works and feels good while knowing it may be inappropriate and hurtful to others. I feel similarly. Perhaps the best thing we can do is to keep talking about it and not pretend it will resolve itself if we look the other way.

Reply

Marie

7/11/2018 11:43:24

After a conversation with a yoga student at the local Shala where I teach I wanted to throw in a point about language. This student mentioned how the ancient (Indian) Sanskrit is a language that places itself outside of our shared (Western) language of English. And additionally in our case here in Denmark – Danish! I know if I use the Sanskrit names for postures most people – regardless of mother tongue– will understand which posture I refer to. This has a practical advantage when you have an international yoga community but also again places the postures in the 'otherness' category. When I refer to a seated forward bend as Paschimottanasana, it is lifted out of the 'mundane-ness' and becomes a movement that is more that a stretch of the hamsting. It somehow has a different intention. At least this is how I feel.

Reply

26/4/2019 06:18:07

I was thinking about the Ashtanga chant/prayer on the way back from the dentists yesterday before I read this because my iPod shuffled to Madonna's track which features it from Ray of Light. First, I thought it was sort of weird, and an epitome of a sort of western commercialisation of sorts and second I thought, I bet Madonna is amazing at ashtanga. But those points you and Alan raise are all fascinating. On Namaste, it's the greeting you get (obviously) on Air India, but as Alan points out about the Hindu majority misusing yoga politically, a friend from the Muslim minority was extremely concerned about the airline proposing to serve only vegetarian food on domestic flights - seeing it as another form of political erasure of her identity. I rather like the ritual in order to open the space to the practice but then I also own mala beads and have a lotus flower tattooed on my shoulder (by a Maori guy in Bondi) so drank the Sydney Eastern suburb koolaid a while ago, but any sort of 'spirituality' in that colonial settler society seems loaded with appropriation...

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Yoga BlogVelkommen til min blog. Arkiver

November 2019

Kategorier

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed